- John Callaway “Jack” Walton — 5th Governor of Oklahoma — official photograph (courtesy of the Oklahoma Department of Libraries). In office: January 9, 1923 – November 19, 1923 (impeached and removed from office)

- Governor Jack Walton’s home during his short tenure in office in 1923 and for some time thereafter. The current Oklahoma Governor’s mansion was not completed until 1928, so governors until that time lived in their private homes. Walton purchased this mansion located in Oklahoma City’s Heritage Hills from oil magnate E.W. Marland under circumstances that were shady enough to prompt inclusion in the articles of impeachment against Walton. On the particular charges regarding the mansion purchase, Walton was exonerated, some believed due to the influence of Marland. Given multiple front doors to the mansion, we are not sure which steps are the ones where Lula “camped out,” or whether this was simply the expression used in family folklore. Regardless, in this mansion, ex-Governor Walton and the newly widowed Lula Berch formed an unlikely alliance against the Ku Klux Klan in Oklahoma.

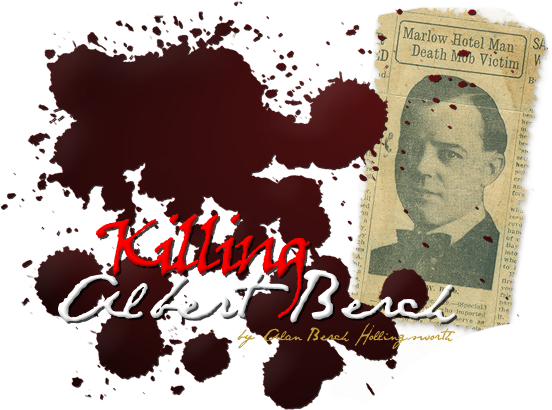

- Newly widowed Lula Berch teamed up with newly ousted governor of Oklahoma, Jack Walton, in an unlikely collaboration to fight the Ku Klux Klan. Desperate for help and protection after the murder of her husband, Lula sought Walton’s assistance in her plight immediately after the murders. Her story was the main feature in The National Anti-Klan Weekly, Jack Walton’s Paper (Vol. 1, No. 11) Sunday, January 6, 1924, only two days after the preliminary hearing for the accused murderers and only 3 weeks after the murders. (original newspaper in the Hollingsworth family collection)

- Built in 1921, the Stephens County Courthouse in Duncan, Oklahoma was nearly new at the time of the murders. The preliminary hearing and both trials were held in this building. Sitting atop the primary brick structure was the county jail, site of surrender of Marvin Kincannon. The building was demolished in 1968 after the current courthouse opened its doors (courtesy of Stephens County Historical Museum)

- Four days after the murders, this photo with caption appeared on page 9 (of 20) in The Daily Oklahoman. This is the only known coverage of the murders that included a photo of Albert Berch. Note there is no mention of the fate of “the negro, Robert Jernigan”(sic). As was commonly the case, both victims’ names are misspelled. The actual newspaper clipping (inset) is Lula’s copy that she included in her “murder scrapbook.” The entire coverage of the story is beneath the picture: Marlow, Dec. 20 – (Special) – Albert W. Birch(sic), who imported a negro into Marlof(sic) to serve as porter in his hotel, in violation of an unwritten law which banned negroes from Marlow, was shot and instantly killed Monday night by a mob which sought to lynch the negro, Robert Jernigan(sic).

- Most of the newspaper clippings in Lula’s scrapbook of “Daddy’s Death” do not include dates or the newspaper of origin, as in the article above, written as coverage of the preliminary hearing. Sometimes, the source was discovered through cross-checking newspapers of the day, or in the case of this article, an ad promoting The Duncan Banner on the flip side.

- Six days after the murders of Albert Berch and Robert Johnigan, headlines in The Daily Oklahoman reveal a common sentiment of the day that the Klan was pro-America while those who opposed the Klan were a blend of radicals, anarchists, communists, socialists and labor unions. In the context of the Jack Walton saga, the charge was made by Fred T. Miller, president of the Oklahoma Constitutionalists, that Oklahoma had been driven to the brink of Civil War in an effort to allow the “Reds” to assume control of the state. Multiple subtitles to the headlines are as follows: Russian Plans to Take State are Blown Up / Months of Secret Effort to Put Communist Forces in Power Bared / Walton “In” On It / Whole Scheme Uncovered By Body That Raised Fund to Fight Jack.

- One of the newspaper clippings from Lula’s “murder” scrapbook. Written after the preliminary hearing on January 4, 1924, this is the only coverage that included a photograph of Lula.

- Twelve days after the murders of Albert Berch and Robert Johnigan (December 29, 1923), Governor Martin E. Trapp made public his stand against the Ku Klux Klan with this headline in The Daily Oklahoman. While serving as lieutenant governor, Trapp was elevated to acting governor during Walton’s impeachment hearings, then to Oklahoma’s 6th governor upon Walton’s conviction and removal from office in November 1923.

- The most thorough coverage of the murders and the aftermath was found in The Duncan Banner. In this January 4, 1924 issue, the headlines are drawn from the preliminary hearing on the Berch-Johnigan murders. The newspaper was a “weekly” at the time, and probably an evening distribution, given that the hearing took place that same day.

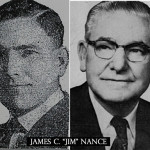

- On January 15, 1924, James C. Nance announced he was resigning his post as a House member in the state legislature, having represented Stephens County. This article in the Daily Oklahoman notes that Mr. Nance was moving to Lubbock, Texas from Marlow. Nance had been editor of the Marlow Review, but had disengaged from the newspaper shortly after the Berch-Johnigan murders. When the Marlow Review failed to cover the events that followed the murders, Lula was openly critical of Jim Nance, not realizing he was no longer connected to the paper. They had previously been on good terms, and Nance was one of the “regulars” who dined at the Johnson Hotel Cafe. Note, too, that the 1924 Daily Oklahoman article labels Nance as a “Walton Apologist,” making any association with the Klan virtually impossible (in addition to Nance’s own published denials of the same).

- Jim Nance returned to Oklahoma fairly soon after his Lubbock experience, emerging as one of Oklahoma’s most highly respected legislators in state history, serving both as Speaker of the House and President Pro Tem of the Senate, inducted to the Oklahoma Hall of Fame in 1955.

- Friday, April 18, 1924 edition of The Duncan Banner covering the start of the first trial. Marvin Kincannon was charged in the murder of Albert Berch and Robert Johnigan, but this trial was for the murder of Berch alone. It took more than 3 days and nearly 200 candidates to seat the jury, the most difficult seating of a jury in the county’s history to that point in time.

- At the time of the murders, the Klan was at its peak popularity nationwide. Anti-mask legislation in many states, including Oklahoma, marked the first step of a downward spiral. In this article from The Daily Oklahoman, February 25, 1924, two months after the Berch-Johnigan murders, Grand Dragon of the Oklahoma Realm, N. C. Jewett, denies accusations by the press that the Klan is losing its influence.

- The KKK near Drumright, Oklahoma in 1922 (courtesy of Tulsa Historical Society and Museum)